Mount Huntington

Since I first laid eyes on it six years ago, Mount Huntington has been in the crosshairs of my climbing objectives. In 2015 I was on a photo assignment in Alaska, and while flying eye to eye with some of the giants of the Alaska Range, Mount Huntington’s incredible and iconic summit pyramid exploded out of the clouds. It was a sight for sore eyes, indeed. I was relatively green to big mountain climbing at the time, but made a promise to myself that one day I would return to climb this stunning Alaskan peak.

Over the last six years I’ve climbed all over the Western Hemisphere, from Alaska to the Peruvian Andes, British Columbia to mountains in my own backyard in California. Finally, after a handful of technical ascents under my belt, I felt like I had the experience I needed. It was time for a crack at my dream mountain.

Mount Huntington is arguably one of the most strikingly beautiful mountains in Alaska, and it does not yield its summit easily. Standing 12,241 feet high, it’s technical walls of ice, rock, and snow attract world class climbers from every corner of the globe. Our proposed route, known as the West Face Couloir, is a 4,000+ foot climb with a couloir of technical ice that stretches 1,200 feet tall. The mixed climbing, exposed traverses, and committing nature of the terrain make this mountain a formidable opponent to say the least.

After months of rigorous training, myself and climbing partner Allen found ourselves passing the time at the local bar in Talkeetna, Alaska, waiting for a break in weather to fly into base camp.

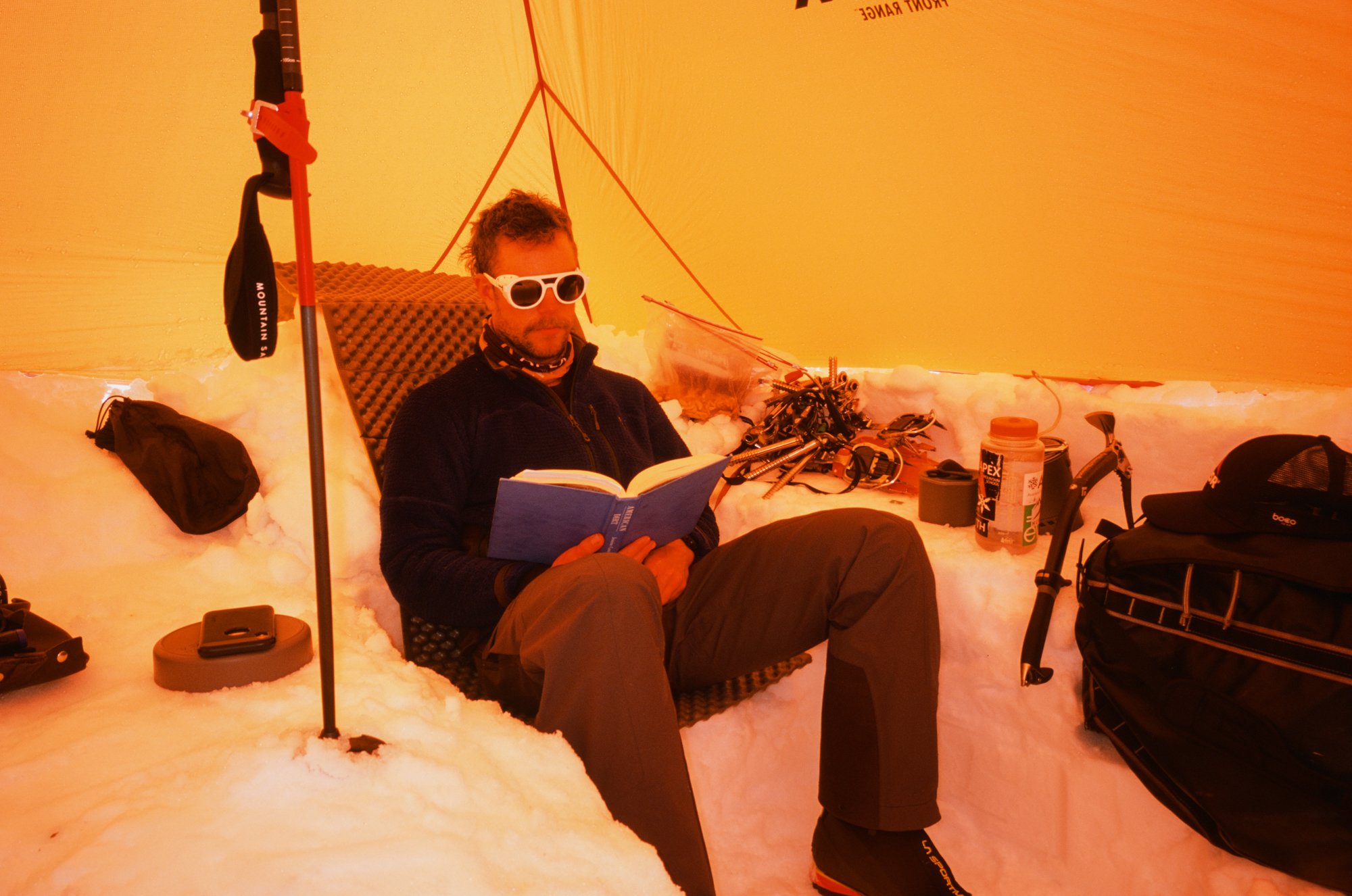

Our weather window arrived after several days, and 30 minutes after takeoff we were landing on the Tokositna Glacier, a journey that would take weeks on foot. The sun was shining and our spirits were high, but the following morning would bring stormy weather that was to last for 4 long days.

On the 5th morning, we began the climb, overjoyed at the forecasted high pressure system over the next three days. The recent storm had dumped at least four feet of snow, making for hours of tedious and exhausting postholing. We winded through a maze of crevasses, and up a challenging bergschrund. The considerable amount of fresh snow put us on edge and we struggled to move as quickly as we could through avalanche prone areas, something that is easier said than done when every step forward seems to equal a few steps backward in the chest deep powder.

We finally reached the start of the couloir, but the tough trailbreaking, slight dehydration, and altitude caught me by surprise and led to an unexpected and rather intense bout of sickness. As I screwed in several ice screws and built our belay station, my nausea led to severe puking and cramping. Allen began to lead the first pitch, a 230 foot long section with a spicy vertical wall while I puked every ounce of food and liquid in my stomach at the belay. I’ve spent my fair share of time in the mountains, but had never had a system failure quite like this. A sizable block of ice bonked me squarely in the head, but thankfully I had just looked down so my helmet received the impact. Another block hit me in the arm, oddly hitting a nerve and leading to even more cramping. Thankfully, Allen’s physical and mental stamina picked up the slack until I was able to keep liquids down, crush some calories courtesy of snickers bars and sour patch kids, and recover my strength.

We climbed through the night, and at 4 AM were forced to take a break on the wall to rest our aching calves and melt snow in order to replenish our water supply. Clipped into the ice wall and resting on a tiny ledge thousands of feet high, this was the epitome of type 2 fun. We rested for a couple hours and then continued up the ice couloir, topping out after a couple more pitches. The most technical climbing was behind us, but the climb was far from over. Another 1,000 + feet involved exposed traversing, mixed climbing, and a long, cold, simul climb on 50 degree alpine ice and deep snow. We gained the summit ridgeline at 2AM, exhausted and cold to the bone. The summit stood just 300 feet above us, but required a committing push up deep snow and overhanging cornices. We opted to pitch our alpine tent for a few hours of rest, and woke up to bluebird skies and thankfully, thawed out fingers. Allen led the final push up the corniced summit pyramid, and just like that, we found ourselves standing on top of the almighty Mount Huntington. There wasn’t a cloud in the sky, and only the faintest hint of a breeze. There are days in the alpine that you only dream of, and this was one of those days.

We concluded our summit celebration of gummies and selfies, and began the long, arduous descent. For the next 9 hours, we rappeled on V threads and old belay stations that we were able to find here and there in the rock. At long last, we arrived back at our base camp. We had left two and a half days before and been climbing for exactly sixty hours.

It had taken six years, but I had finally climbed Mount Huntington. I crawled into my sleeping bag, tired and overjoyed, with enough type 2 fun to last me for a while.